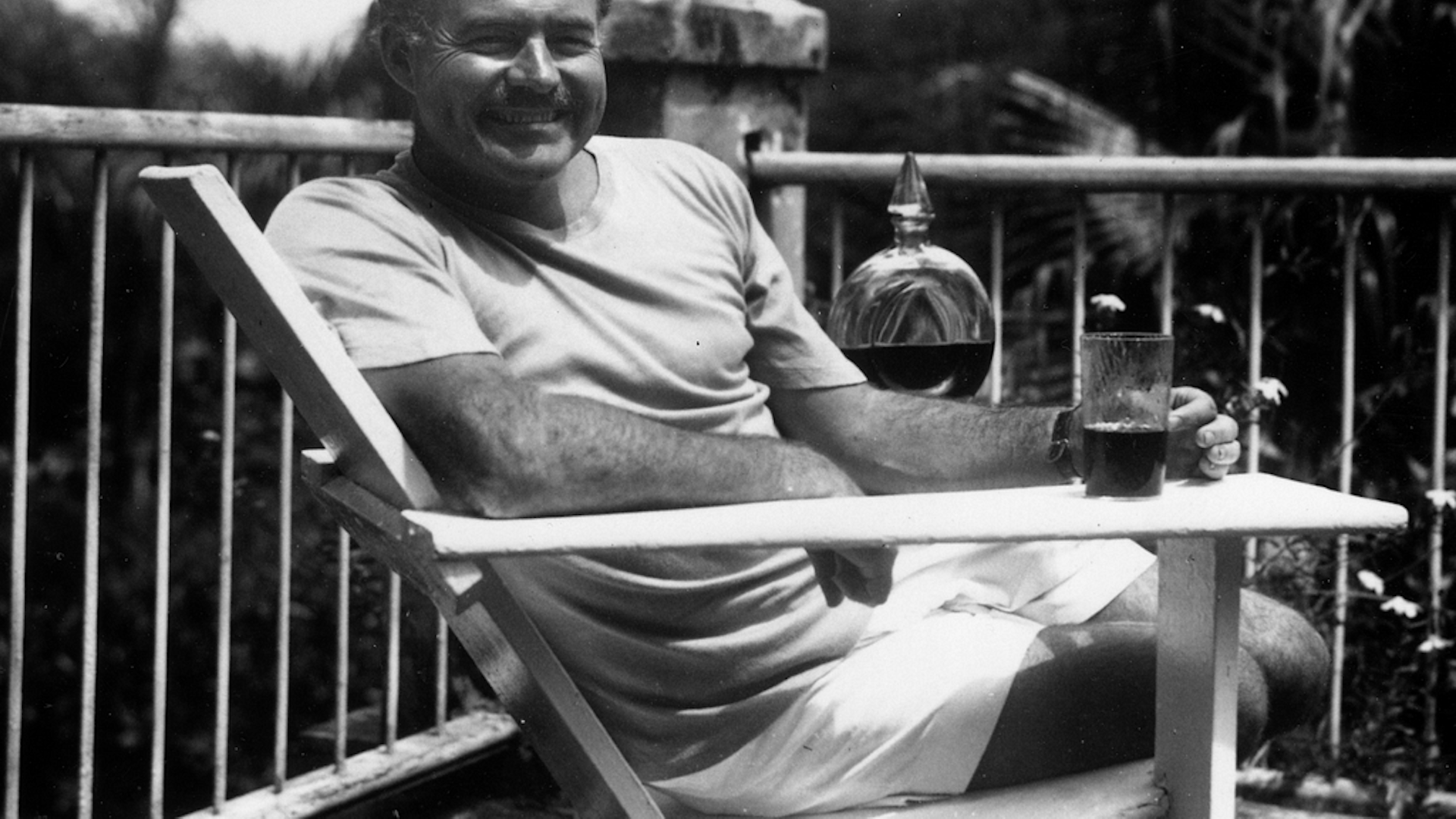

Born in the Cuban heat at the end of the 19th century, the daiquiri is much more than just a cocktail. This legendary drink, beloved by Ernest Hemingway, accompanied the writer in creating a body of work that earned him the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1954.

Cuban Origins

In 1898, near Santiago de Cuba, American engineer Jennings Cox invented the daiquiri out of necessity. Using local rum, lime, and sugar, he created a mix that would captivate both miners and writers alike. A century later, this trio of ingredients would become a metaphor for Hemingway’s style: simple, powerful, and balanced.

Hemingway and Cuba: The Nobel Laboratory

Hemingway’s Cuban adventure began in 1928 during an impromptu stopover. The island became his "third sacred place" after Spain and Michigan. Settling in Finca Vigía in 1940, he wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea—the latter earning him the Pulitzer in 1953 and paving the way for the Nobel Prize.

"Cuba taught me to fish for words as one harpoons a marlin."

Letter to Charles Scribner, 1951

El Floridita: The Antechamber of the Nobel

At the El Floridita bar, Hemingway consumed up to twelve Papa Dobles a day. This sugar-free daiquiri—double rum, pure lime—became his creative fuel. Bartender Constantino Ribalaigua refined the recipe alongside the writer, much like an editor polishes a manuscript.

In 1954, the Nobel committee recognized this symbiosis between intoxication and lucidity: “His art of transforming adventure into universal truth” drew as much from Havana’s bars as from the Gulf Stream.

Cuba, A Liquid Muse

Hemingway’s obsession with the original daiquiri (rum, lime, sugar) mirrored his literary pursuit:

Deceptive simplicity: 3 ingredients / short sentences

Inspiring terroir: The island appears in 5 of his major novels

Creative alchemy: “A good cocktail should hit like a perfect sentence.”

This philosophy reached its peak in The Old Man and the Sea, written in Cuba and cited by the Nobel committee as "a masterpiece of thematic concentration."

Legacy: When History Raises a Glass

Today, the daiquiri’s return to its roots echoes Hemingway’s literary heritage. As one expert notes: “His Nobel is 40% Cuban—without the fishermen of Cojímar and the nights at El Floridita, would he still be a literary giant?”

Sipping on a modern-day Papa Doble, one can still taste the essence of this unique pact: a writer, an island, and the cocktail that etched them into history.