The Formation and Role of Esters in Spirits

Esters play a central role in shaping the aromatic profile of spirits. These volatile organic compounds, formed through the reaction of alcohols and acids, are responsible for many fruity, floral, or spicy notes. Their presence and balance contribute significantly to the sensory signature of each spirit — whether whisky, rum, or Acerum. Esters are formed throughout the production process, especially during fermentation, but their distribution and evolution also depend heavily on distillation and aging.

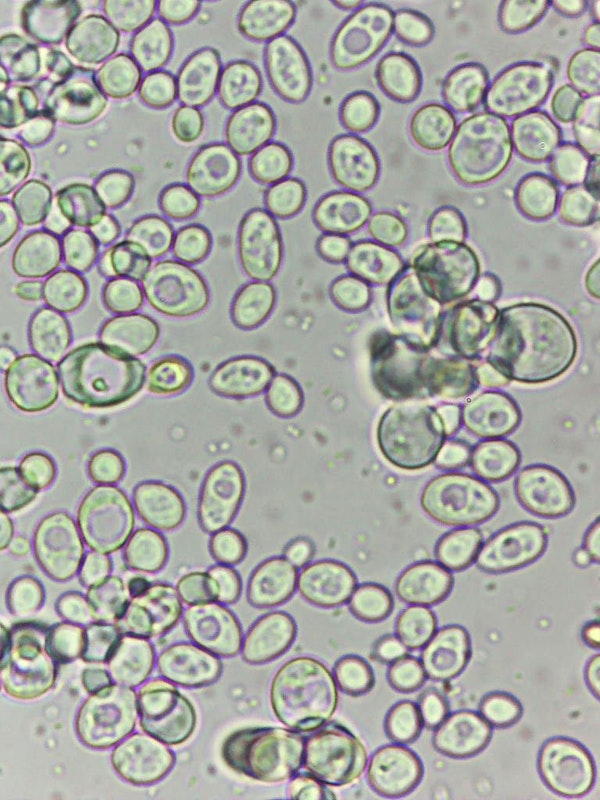

Fermentation: The Cradle of Esters

Fermentation is the foundational step in ester production. During this process, yeast consumes the sugars in the mash to produce ethanol and carbon dioxide. At the same time, it synthesizes a wide variety of aromatic compounds — including esters — through specific enzymatic reactions. These are mainly catalyzed by alcohol acetyltransferases, enabling the union of organic acids (produced by the yeast or found in the substrate) and higher alcohols.

Several factors influence the type and quantity of esters formed:

Yeast strain used (some strains naturally produce more esters)

Fermentation temperature — typically between 25–30 °C for more aromatic expression

Fermentation duration

Agitation in the fermenter and nitrogen nutrition

By adjusting these parameters, the distiller can begin shaping the product’s aromatic identity from this very first step.

Distillation: Selection, Concentration, and Recycling

While fermentation creates esters, distillation acts as a filter and an amplifier. It allows for the selection, concentration, or removal of certain esters depending on their volatility, molecular weight, and the still’s design.

Light esters (e.g. ethyl acetate — pear, solvent) are found in the heads

Heavier esters (e.g. ethyl butyrate, ethyl hexanoate — pineapple, strawberry) appear in the tails

The cut between these fractions defines the aromatic profile of the distillate’s heart.

A key but often overlooked factor is the recycling of heads and tails, a common distillery practice:

Recycling heads enriches the still with volatile esters and can boost light fruity notes

Recycling tails, rich in fatty acids, can generate new esters if ethanol is present — especially at high temperatures

If well managed, this technique fine-tunes the aroma profile. Poorly managed, it may create imbalance or exaggerate certain notes (solvent, wax, over-fermentation).

Other parameters that influence ester distribution:

Still shape and height

Reflux rate

Distillation speed

For example, a pot still retains more heavy compounds than a highly rectified column still.

Barrel Aging: Transformation and Complexity

Once the distillate is produced, it enters the aging phase — often in oak barrels — which allows esters to evolve further. This stage, sometimes lasting years, leads to both the formation of new esters and the transformation of existing ones.

Key processes include:

Formation of new esters: Ethanol reacts with organic acids from the wood (acetic acid, phenolic acids, etc.) or from oxidation

Hydrolysis and recombination: Some unstable esters break down and re-form with new acid/alcohol pairings

Selective evaporation: The most volatile esters may evaporate through the barrel, slowly shifting the aromatic balance

Barrel characteristics (new or reused, toast level, wood origin) strongly impact the final result. This is when notes like ripe fruit, vanilla, or spice may gain roundness and complexity.

Aromas at the Heart of a Spirit’s Style

Each ester contributes to a specific aromatic dimension. For example:

Isoamyl acetate – ripe banana

Ethyl acetate – pear, solvent (at high concentrations)

Ethyl hexanoate – green apple, strawberry

Ethyl butyrate – pineapple, tropical fruits

Phenylethyl acetate – rose, honey

In some "grand arôme" rums — especially of Jamaican tradition — ester levels can exceed 1000 g/hLAA, creating uniquely intense flavor profiles.

Conclusion

Though invisible to the eye, esters profoundly shape a spirit’s personality. Their presence and balance result from a complex chain of technical decisions — fermentation, cutting, recycling, aging — precisely orchestrated by the distiller and cellar master. They are the silent architects behind the aromatic symphony in every sip.